Direct Primary Care Enhanced by POCUS:

A Conversation with Dr. William Steelman

Part 2

Dr. William Steelman

DO, FACOI

Luke Baldwin

VP of Global Marketing, EchoNous

This is the second half of our interview between Luke Baldwin, VP of Global Marketing at EchoNous, and Dr. William Steelman, who digs deeper into the details of Direct Primary Care.

If you haven’t read part one, you can do so here.

[Note: This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.]

The Role of POCUS in Direct Primary Care

Luke Baldwin: Yeah, it’s amazing to hear the feedback directly from your patients. Access to care, cost reduction, and human touch are significant challenges people grapple with. Access to care, in particular, is a huge topic. So, it seems like you’re really onto something with the direct primary care model, solving real problems, which is fantastic.

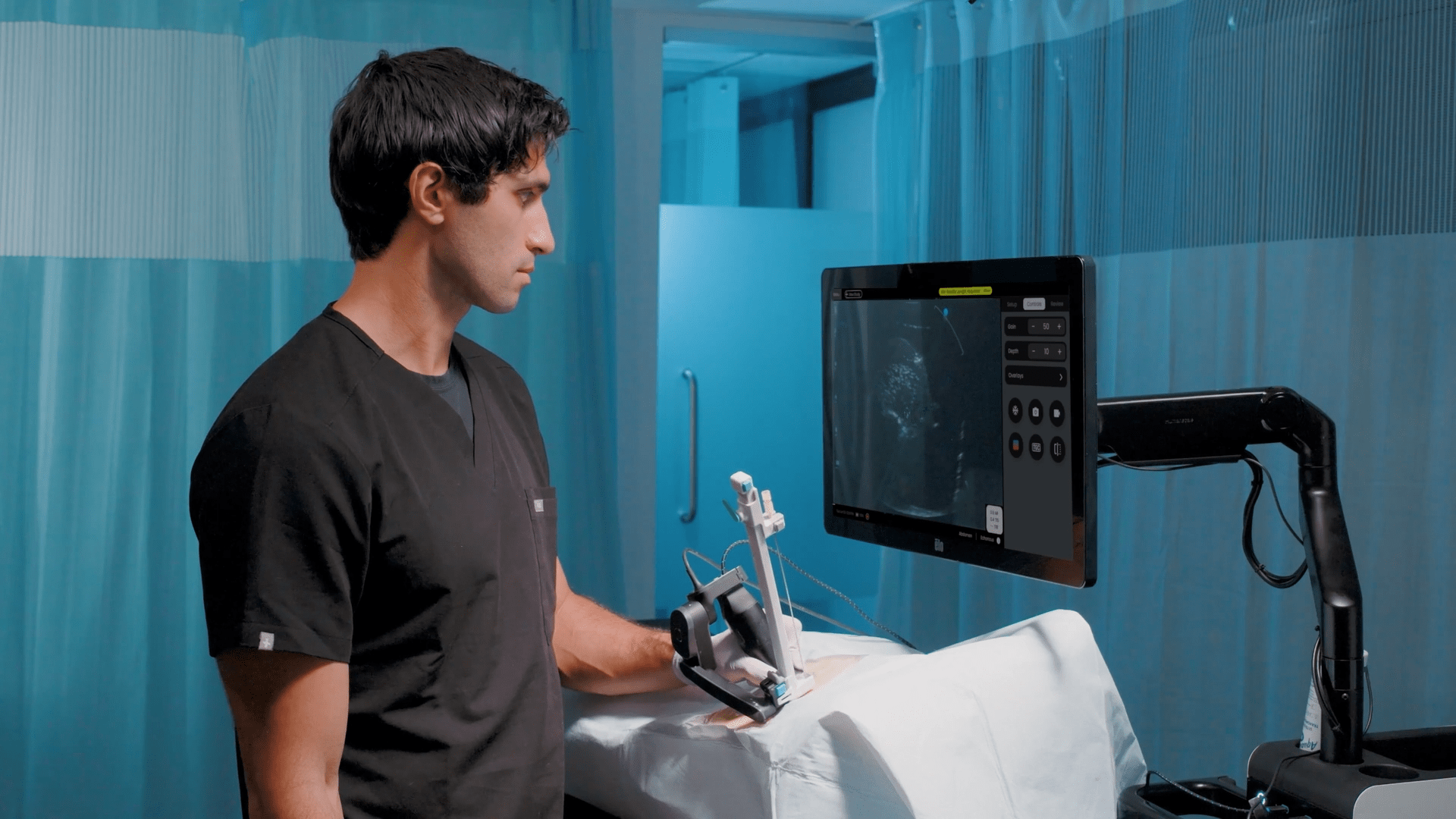

Speaking of solving problems, our conversation started because you purchased an ultrasound system from us, the Kosmos product. Can you share your journey into ultrasound and what led you to choose our system? What specific problem were you looking to address with it?

William Steelman, MD: Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) started gaining traction around 2009, although it had been around for about 10 to 15 years prior, mainly used in operating rooms and emergency rooms for procedures like line placements. However, it wasn’t common for primary or ER doctors to use it bedside until then, except for those in high-pressure ERs doing quick exams before sending patients off for CT scans.

I found POCUS fascinating because of my interest in technology, even though I didn’t receive formal training until residency in 2009. Then, we started using ultrasound more extensively, sometimes borrowing machines from the ER. It was versatile, allowing us to perform procedures like ultrasound-guided central venous catheter placements and many others. Still, the technology lends itself to experimentation. It can be playful learning because it is so non-toxic and easy to use, and while the gel is a little weird to clean up after the procedure, it’s not invasive and a quick and easy way to get preliminary answers.

Now, do I think in the future, this technology will continue to increase and become a mainstay as they use newer technology signals? Yes, I think AI will transform this radically over time.

I was waiting for the POCUS technology to come out to the point where it made sense to buy it and have it with me always, probably since I started medical school. I always wanted to have one of these in my pocket, where you can put a little device on someone and find and confirm an answer you have suspected for a while.

In internal medicine, one of the primary uses of ultrasound is probably the transthoracic echocardiogram, which your product (Kosmos) is designed to provide a preliminary answer for. It may not offer the same depth as the hospital system, but it doesn’t need to. I can still detect pericardial fluid, compare prior baselines with current scans, identify pleural effusion, spot early signs of pneumonia or pulmonary edema, and measure aortic diameters. While I haven’t mastered gallstone detection yet, I’m still exploring its capabilities in that area.

But the idea of confirming some of these things without sending them through a high-dollar test at the hospital, which is $300 to $1000 in my area, is amazing. You can go online; shout out to my guys who made the BILLY app. They collect information on how much insurance companies charge patients for particular DRGs and procedures. So, you can look up in your local area how much these procedures cost patients in real life, and it is astounding how much extra unneeded cost you are generating.

So, we primarily try to use this kind of thing to determine if you have worsening heart failure or if you’re developing pneumonia. These are difficult things to determine one way or the other in the hospital. They sound very similar. And so, to trained ears, you can hear the difference with the stethoscope, but then you’re talking about medicine that’s, I don’t know, pre-1800s, and it’s a complex tool to train people on. It’s a difficult tool to get a reliable answer between providers.

Frequently, we rely on lab tests and formal echocardiograms to tell us which way to go. But if I can use a preliminary test and already know the patient’s history, it’s a slam dunk. Easy. I’ll give you an extra diuretic. I prevent you from getting hospitalized four days later. Very easy.

Luke Baldwin: Have you owned other handheld devices in the past? Or is this your first?

William Steelman, MD: This is my first personally owned or business owned [device]. I’ve always used the major products in hospitals and various companies, but they’re the more robust, you know, $50,000+ machines; some of them are way more. But those are unobtainable from a small business, small office, or even personal standpoint, but something like this, it’s an easy return on investment because I can use it to provide care directly to my patients and save them money, which is the whole business model.

Luke Baldwin: How does the Kosmos compare to what you could get done with those more expensive systems?

William Steelman, MD: So, what’s my experience with this? Well, I’ve always had to rely on the equipment at hospitals, which you practically have to beg for. You might get access once a week if you’re lucky. Then there’s the hassle of returning it to the ER, which takes up hours of valuable time. Most people just end up skipping it altogether. But with this portable device in my pocket and my iPad for electronic medical records, I have everything I need right at my fingertips. It’s all about accessibility. Why choose this product over others? Sure, there are handheld devices out there, but their image quality isn’t up to par, so they’re not as valuable in the end.

Luke Baldwin: We’ve heard some good feedback on that front. What do your patients think about it? Bringing ultrasound into their homes or the clinic is quite a change. I’d imagine most haven’t had an ultrasound from their primary physician in the past.

William Steelman, MD: I remember this one guy who stopped me when I explained the AI capabilities for preliminary readings and anatomy labeling and asked, “Is this the future?”

I said, “Absolutely!”

AI is truly fascinating, and I could talk about it all day. Recently, I attended a conference where they discussed AI in healthcare—it’s a hot topic right now. Essentially, it’s saving us time and allowing us to focus more on patient care. As doctors, that’s always been our goal.

One of the biggest challenges of being a physician today is feeling like you could do better but not having the means to do so. They call it “moral injury,” and it leads to burnout, stress, and a shortage of providers. COVID-19 has only exacerbated this issue. But having this kind of tool at my disposal, where I can quickly confirm a diagnosis or track a patient’s progress, makes a significant difference.

Patients really appreciate it, too. They love having a doctor who’s up to date with the latest technology and advancements. Nowadays, patients expect more from their doctors—they’re not satisfied with someone behind a desk relying on outdated textbooks. They come to me with questions they’ve found online, seeking advice and reassurance, and I have to be ready to answer. It’s challenging, but it’s also rewarding. I enjoy staying informed and keeping up with my patients’ needs, even if it means putting in extra effort to stay ahead of the curve.

The Direct Primary Care Approach

Luke Baldwin: I can see how it could be beneficial when someone comes in, especially if they have a family history of heart problems and experience unusual pain over the weekend, causing them to feel nervous. I bet just using the probe to assess their heart condition and reassure them that their heart is healthy can provide them peace of mind.

William Steelman, MD: Right.

Luke Baldwin: So, how many patients can you see to provide that kind of time and in-depth level of care?

William Steelman, MD: One of the other tenets of direct primary care, in general, is that we see a limited panel. So, a traditional internal medicine physician in an office or family practice doctor in an office will have a panel of anywhere from 2,500 to 3,500 patients, and they’re seeing 20 + a day every single day that they’re open Monday through Friday, no holidays, no weekends.

But, in direct primary care, because we’re a membership model, and we don’t charge for copays, return visits, and things like that, we only cap around 500-600. I think the last time I heard, on average, was around 385 on any given panel.

The cap that I set is around 600. If I saw more people than that, I could, but then I couldn’t offer them the same access and time to spend with me, and it would make doing things like bedside ultrasound and comprehensive exams less viable. So, on average, the family practice world is about 1% of your panel which will come through your door every day. So, capping at 600 puts me at about six interactions a day, about 50% tele-visits and 50% office visits. So that’s about average.

So, because I’m new and building my practice, I’m still moonlighting and doing that part-time, but I’m also building the practice up, and as the weeks have passed, I’ve only been open about two months, you know, I have 3-4 days a week that I have a full schedule, so it’s working.

Luke Baldwin: Yeah. Congrats. That’s great.

Does this model alter financial incentives for physicians? Specialists often earn more, like neurologists, but could this approach shift the balance, enticing more doctors into primary care and benefiting the system?

William Steelman, MD: Oh yeah, for sure. No one should look at this and say that people aren’t going to be people and that, you know, financial incentives aren’t going to incentivize people because they will. Anytime you inject money into a system, you get more of whatever you’re buying.

So, whether it’s government funds or private business models, people get what they pay for. So, when you’re paying your doctor cash, I do not have to beg an insurance company to get paid appropriately. I’m not begging them to give me fewer patients daily. The flip of that coin is that I have to go out there and promote my business constantly. I’m learning, but I’m not very good at that yet. I have an Instagram account, and my wife is my practice manager, which is pretty awesome. We make advertisements, and we promote the business in general. I have to educate people that they have an option.

Other than paying these horrendous fees for small business insurance right now, the average employer will pay almost $22,000 per employee for a standard PPO [Preferred Provider Organizations] because of Blue Cross, United Healthcare, Cigna, Humana, Aetna, all these guys, United, represents most of it. They now own about 10% of all doctors nationwide, so you can see where all this consolidation has created these forces on the doctors where you just don’t want to deal with all the paperwork they’re sending you.

This [direct primary care] system allows me to operate outside of that, and [patients] can still bill their insurance for procedures and imaging things, etc. You can still run your insurance; you can run your, as they call it, “card” for lab images, medications, etc. And that saves money. It’s triple tax preferred. It’s fantastic. So, you can operate with insurance. You can operate outside insurance, and being independent means I can also set healthcare plans and goals for patients that would otherwise be ignored. I’m a big fan of using continuous glucose monitors on people who are not diabetic or pre-diabetic, which would never get authorized for them. It’s useful in preventing this slip into diabetes; we have a huge epidemic of this. I could go on for years about that one, but you know, the access to care really changes lives, and that’s huge.

In terms of salaries, going back to the original question, I think from what I’ve read and what I’ve heard from the people who have founded this, this whole direct primary care movement, they say it’s about a 30% increase in physician pay because it’s cash-based. I’m not paying a biller. Billers generally want to collect something like 5% of your total earnings. They take that as their cost in order to process your billing. And that’s on top of how much you’re getting as a negotiated rate with the insurance companies, and they don’t have any incentive to negotiate with me. I’m small potatoes. I’m 600 people, you know, they’re not going to bend over and give me $20 bucks extra per patient, you know, because I’m not bringing them thousands of patients, you know? So that’s part of it, for sure.

Luke Baldwin: Can you clarify how Medicare fits into your payment system? I’ve always been a bit confused about it. I know there are reimbursement codes for procedures like limited echos, but do you handle billing for Medicare, Medicaid?

William Steelman, MD: Direct primary care, we don’t bill insurance that includes Medicare. We don’t take their money or bill for them. We don’t also ask for their permission to do these things because you typically have to have the administrative burden of a specific CPT code or a certain DRG. You have to get all the paperwork to get it to be qualified even to be an option, and the people who decide that are not deciding it because it’s the best medical decision; they’re deciding because of the cost.

And if I remove that entirely and say, well, I’m going to use it, and I’m not going to charge them, then Medicare is OK with that. But I don’t need to bill Medicare anyway, so I’m not worried. I can see patients on Medicare, you know, as an opted-out physician, you know, without any issues.

Medicare saves money on it, so they should love the interaction, and the BUCA’s makes a tremendous profit from this in the end because their patients are in the hospitals 50% less, where the highest cost of medical care happens. I could also give you many examples of that.

[For example], the Milliman Report is an actuarial company that does cost analysis for accountants and things like that. They took around several hundred people in a cohort and followed them for a year as they initiated a direct primary care center.

The overall benefit, in general, is a cut-down. I can read you the stats and send you the report, but it’s about a 40 to 50% decrease in ER and hospitalizations, which is a major line item. Now, in that report, you’ll quickly notice that when you go right to the executive summary, they say that the overall expenditure was increased by 12.3%. If you suddenly make it possible to get things, people will get more things.

We learned this with the Affordable Care Act: as you suddenly turn up access to care, more care needs to be done. But the benefit to getting early care over waiting until they’re sick and then paying for it is outrageous. It’s 6X for pre-diabetics and 10X for people with diabetes in terms of cost to manage somebody to care for somebody. If you wait until they’re so sick that they cross the threshold, then you just explode your costs. We see this every single day, every single day, and if you don’t believe in metabolic syndrome, talk to me again. I’ll talk your ear off on it because everybody in America is fighting this battle, whether they know it or not.

Avoiding the standard American diet of processed foods and added sugar is about 80% of the battle, so if I just start there and stick to that, I won’t lose a lot of people. But if you’re eating fast food and drinking sugar sodas, there is an unbelievable correlation, and people know this. So, it’s a big thing, and you can’t realistically expect people to change their diet and lifestyle by meeting them once a year and telling them you should exercise—that’s never worked once.

Luke Baldwin: If a patient is only seeing a primary care physician once a year, its like, who are you? I’ll see you for seven minutes. You’re going to tell me [the patient] to change?

William Steelman, MD: Exactly. See, now you get seven minutes. It isn’t cutting it. So, if I spend an hour with you now and then, we can catch up again in three months and pair continuous glucose monitors, look at your ultrasound results one more time, look at your weight, your circumference. We get a DEXA scan to look at your visceral fat. We do all these things. We’re changing the game regarding outcomes and overall cost lengthwise.

Luke Baldwin: In marketing, something called the “Rule of 7″ suggests that customers need to see a message around seven times to increase buying behavior.

William Steelman, MD: The average insurance interaction lasts about three years due to job changes. Unfortunately, physicians often become tied to networks with specific insurance providers. So, as competent as a doctor might be in one role, they may not be in-network for a patient’s next insurance plan if they switch jobs. This disconnect creates a problem where long-term care isn’t prioritized. If it costs money upfront, individuals tend to pass the responsibility to the next person, sometimes without even seeing the bill.

From a business and insurance perspective, doctors are aware of this situation. Many physicians are pessimistic, assuming that no one will change or take action. This mindset stems from not knowing the patients personally. Establishing a personal relationship changes everything; it builds trust and enhances care. That’s why returning to what we’ve always wanted is crucial. When I started this journey, I asked myself, “What do I want from my position?” And then I realized, why not make it go that way?

Luke Baldwin: It’s cool to hear your ideas and vision for how healthcare should improve and the equipment we create because that’s ultimately what drives us.

Our main goals are to improve access to care and enable earlier diagnosis and treatment. We invest in AI because we believe that if physicians have access to imaging and know how to use it, they can uncover health issues that might have gone undetected. Making ultrasound easier to learn and adopt and less intimidating is one way to achieve this goal. If more people can use it, they can perform scans and identify health issues earlier, such as heart conditions that people might not be aware of. As Dr. Peter Fitzgerald discussed, identifying problems early can help “unbend the curve before it’s bent” and enable earlier treatment and lifestyle changes.

William Steelman, MD: Right.

Luke Baldwin: We appreciate your perspective. It’s great to hear from you, and I look forward to continuing to follow your progress.

William Steelman, MD: I’m really looking forward to getting my hands on the linear probe as well because I am trained in ultrasound lines, and there’s ever-evolving technology for ultrasound place lines. We manage a lot of PICC lines in internal medicine; placing PICC lines is a big thing, and getting access to scheduling to do that is currently mostly run through the hospitals, which is a nightmare.

But every infectious disease doctor out there needs somebody running and managing these things, and they do it themselves to some extent, and then they pour the rest into the hospital. You know, it’s these kinds of things are where I’m looking, you know, down the road. We had talked before about ultrasound probes, which can see smaller, finer vessels. We talked about where that might go one day.

Luke Baldwin: Absolutely! I can definitely see how having the ability to examine joints and quickly identify issues like tears or fluid buildup would be incredibly valuable in your practice. And yeah, the linear probe would definitely excel in those situations.

William Steelman, MD: I hope I answered your questions. It’s impossible to say how you will motivate new primary care physicians if you’re not showing them that things will be different than they are now; it has to change. I think it is changing, and I believe this model is changing.

When people see that direct primary care physicians can do medicine the way that we’re trained, the way we want to provide medicine and the way patients want it, it makes a lot more sense.

Luke Baldwin: I love it. Very cool. Thank you. It was great chatting, and we’ll catch up again soon.

William Steelman, MD: Thank you. Appreciate it.

To learn more about Kosmos, contact us today!