The Evolution of Ultrasound in Emergency Medicine Practice

Over the past decade, ultrasound has revolutionized emergency medicine, providing real-time bedside diagnostics to guide clinical decisions in time-sensitive scenarios. With this direct access, ultrasound provides the emergency physician the ability to immediately evaluate, diagnose, and treat at the bedside without time delays or patient transport that are inherent in traditional imaging modalities. Grasping the history of ultrasound is key to understanding its current and future role in emergency medicine.

This technology originated in radiology in the 1960s and 70s and has matured into lean, point-of-care devices. The decades of ultrasound addition to emergency practice have been fueled by both creativity and learning. The evolution of technologies and clinical practices has been mirrored by the development of emergency ultrasound training, which has become a fundamental aspect of emergency medicine education worldwide. This article provides a glimpse into the evolution of ultrasound from a therapeutic device to an integral diagnostic tool, how its applications proliferated within emergency medicine, and how its history remains the basis of continued forward momentum.

Table of contents

- The Evolution of Ultrasound in Emergency Medicine Practice

- The Origins of Emergency Ultrasound: A Global Historical Perspective (1960s-1980s)

- Emergency Medicine Embraces Ultrasound: The 1980s-1990s

- Formalization and Expansion in the 2000s

- The Role of Lung Ultrasound in Emergency Medicine

- Ultrasound History Meets Modern Innovation: 2010s to Present

- Emergency Ultrasound Training: Current Challenges and Future Directions

- Conclusion

- References

The Origins of Emergency Ultrasound: A Global Historical Perspective (1960s-1980s)

Medicine’s ultrasound history started in the middle of the 20th century, and the technology was first used within the walls of radiology departments. Early machines were big and fixed, so people had to go to a proper imaging center, and trained technicians did the scans, and radiologists read the results. This model was technician-performed and consultative, which promoted standardization but limited bedside availability and turn-around time, particularly in acute care settings.

However, an alternative model arose in various parts of Europe and Asia, especially in Japan, where physician-performed ultrasound began to take root. In this approach, the treating physician performed the ultrasound at the time of the clinical encounter, enabling simultaneous, real-time correlation with patient symptoms and presentation. This flexibility set the stage for what we now refer to as point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS).

Over this period, sub-specialities like obstetrics, gynecology, cardiology, and surgery started using ultrasound for more particularized use cases, widening its clinical appeal even more. Importantly, Japanese and European trauma surgeons used early ultrasound to detect internal bleeding, especially in unstable patients, which was a crucial step in expanding its emergency use.1

These key decades created two divergent practice models that continue to shape worldwide POCUS utilization in modern times. This history of ultrasound is critical for framing how the process of emergency ultrasound training evolved to adapt to varied clinical contexts.

Emergency Medicine Embraces Ultrasound: The 1980s-1990s

Ultrasound in acute care and emergency medicine

Emergency medicine emerged as a standalone speciality in the 1980s and 1990s, paving the way for ultrasound integration into acute care. During this time, portable ultrasound devices began being introduced into trauma settings, especially for early Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma (FAST) exams.

These applications showed the value of ultrasound in quickly identifying internal bleeding and facilitating life-or-death interventions. Handheld ultrasound devices were game changers, an example of which was worked on by Schwarz and Meltzer in 1988 to prove that bedside cardiac imaging was feasible even with low image quality.2

At the same time period, the concept of Emergency Medicine Ultrasound (EMUS) was evolving, and clinicians began to recognize the diagnostic and procedural usefulness of Point-of-Care Ultrasound (POCUS). In the beginning, “emergency ultrasound training” was informal, conducted by a handful of pioneering emergency physicians who appreciated the game-changing potential of bedside imaging. These trailblazers urged broader utilization of ultrasound and started teaching colleagues and trainees, leading to a grass-roots growth of skill and interest.

As the technology became better and early success stories spread through emergency practice, ultrasound became increasingly integrated into emergency practice. In doing so, these advances not only established ultrasound as both a diagnostic adjunct and a cornerstone of emergency medicine education and patient care but also laid the groundwork for future formalization and widespread adoption of this technology.

Formalization and Expansion in the 2000s

The 2000s were a turning point in the formalization and growth of emergency ultrasound in both clinical practice and medical education. Institutions like the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) released landmark guidelines defining and constructing use for emergency ultrasound, and organizations’ support aided the implementation of standard care protocols 3,4. These recommendations necessitate the inclusion of emergency ultrasound training in residency and fellowship programs so that clinicians can be trained to appropriately perform point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS).

In this time frame, the five core domains of Emergency Medicine Ultrasound (EMUS) emerged; these were resuscitative, diagnostic, procedural guidance, symptom/sign-based, and therapeutic applications 5. These domains specified the range of clinical situations in which ultrasound could offer rapid and actionable information. Its wider application for the assessment of dyspnea, chest pain, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), intrauterine pregnancy (IUP), and Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm demonstrated the expanding clinical impact of this technology.

Simultaneously, credentialing requirements and structured curricula were created to standardize competency across institutions. While progress has been made, education and skills assessment continue to vary between residency programs, suggesting that further improvement is needed in training methods. 6,7. However, this decade proved ultrasound to be an essential tool in emergency medicine and laid the groundwork for subsequent innovation and worldwide acceptance.

The Role of Lung Ultrasound in Emergency Medicine

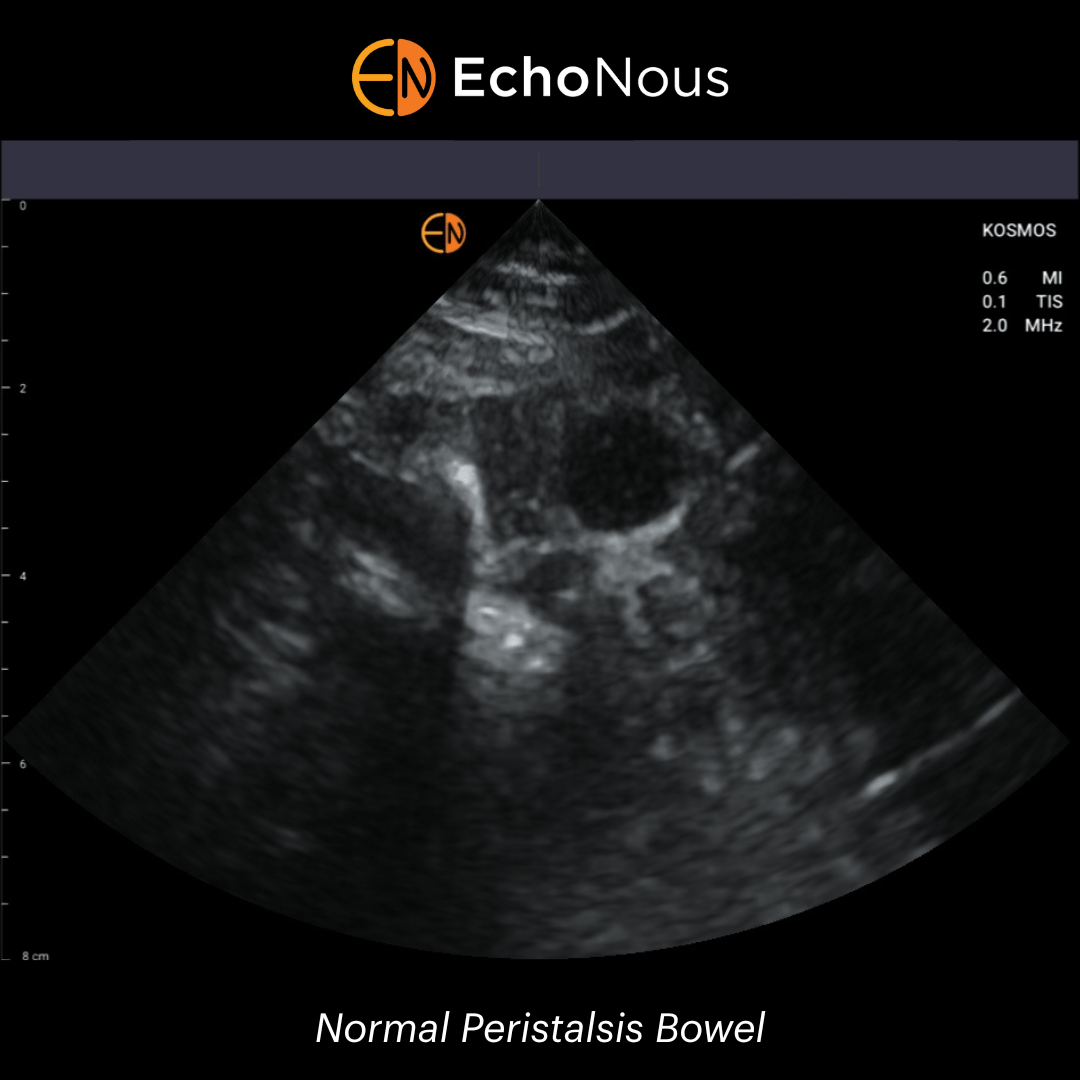

Lung ultrasound (LUS) has transitioned from initial skepticism to common clinical application in emergency medicine. Its use was limited at first because of fears that air-filled lungs would interfere with ultrasound imaging. The advent and clinical validation of artifacts expressed with a plurality of B-lines that had baffled clinicians until then caused a paradigm shift in lung sonography 8,9

LUS is now widely applied to assess multiple pulmonary pathologies during emergency triage. There are also a few visual aids that you can use to help with a diagnosis; B-lines can help identify pulmonary edema and the absence of lung sliding, and the ‘lung point” can detect pneumothorax 10,11.

Fundamentally, LUS has been a paradigm for the utility of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS), especially for acute and chronic heart failure, allowing for real-time bedside evaluation of pulmonary congestion 12. In a 2024 article, Osterwalder identifies LUS as one of the impressive new frontiers in EMUS, emphasizing its incorporation into contemporary diagnostic regimens.

Ultrasound History Meets Modern Innovation: 2010s to Present

The last decade-plus, from the 2010s to the present, has been an exciting time filled with innovation in emergency ultrasound, combining its historical framework with the current frontiers. Recently, ultraportable ultrasound devices have revolutionized point-of-care imaging by expanding access and mobility in high-resource and remote environments. Simultaneously, tele-ultrasound capabilities have allowed for real-time remote guidance and interpretation, further widening the reach of ultrasound into underserved areas and improving global training initiatives.

The introduction of technological innovations, including AI-guided image analysis, elastography for assessing tissue stiffness, advanced doppler mode for vascular evaluation, and cloud-based solutions for image sharing and storage, improved the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound considerably. Smart glasses are just one of the innovations inspiring a future of ultrasound-guided procedures in wearable tech 1.

It has also been a time of conceptual change in medical education and practice, of what is now widely referred to as the integration of ultrasound into the physical exam: moving “from stethoscope to sonoscope”. Accordingly, point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is now perceived to be not an adjunct but a core clinical skill.

Importantly, the continued focus on global reach and customized emergency ultrasound training in accordance with varied healthcare system requirements is vital.1 It illustrates how these advancements and pedagogical approaches are revolutionizing emergency medicine ultrasound (EMUS) in a way that keeps EMUS relevant and productive in clinical scenarios.

Emergency Ultrasound Training: Current Challenges and Future Directions

While advancing towards a more standardized and competency-based future, challenges in emergency ultrasound training persist. In recent years, there has been a great emphasis placed on competency-based rather than time-based certification, confirming demonstrable ultrasound use proficiency before independent practice 5,6.

In order to overcome geographic disparities and limitations in access, simulation-based education, tele-supervision, and remote training models have been incorporated into many programs for the benefit of underserved and rural areas 13,14. These tools can help broaden learning opportunities without sacrificing quality and oversight.

Despite widespread adoption and evaluation of efficacy, variability in training in US emergency ultrasound education and credentialing across countries and residency programs underscores the need for international consensus 4,7. Wide-ranging frameworks have been developed to guide ultrasound education from undergraduate medical education to continuing professional development, cementing the position of the technology at the heart of emergency care 15.

Extensively enabling clinical decision-making while not letting misapplication or overuse occur through appropriate training is essential for maintaining the integrity of diagnostics. Curricula that integrate critical reasoning and appropriate use criteria are more effective in producing responsible ultrasound practitioners 16.

The challenge going forward will be to optimize the role of emergency ultrasound training in a global and rapidly advancing medical environment through improved quality, accessibility, and standardization of education.

If you’re an emergency physician, educator, or trainee, deepen your understanding of ultrasound’s roots to help guide its future. Advocate for structured emergency ultrasound training programs and explore new applications that enhance patient care at the bedside.

Conclusion

Ultrasound has revolutionized emergency medicine. What was once a specialty imaging modality is now a staple of real-time, point-of-care diagnosis.

Its evolution from the radiology departments of the 1960s to the hands of emergency medicine physicians across the globe is a testament to significant breakthroughs in clinical care, education, and technology that have made this possible.

Now, emergency ultrasound has evolved beyond a diagnostic modality to stand as an example of how innovation combined with a pragmatic, evidence-based approach to education can help improve the standard of care.

The unfolding of ultrasound history with innovative applications and systematic training in emergency ultrasound as new end-use technologies become available and access to these technologies grows globally remains a critical factor that defines and drives the Speciality into the future.

References

1. Osterwalder et al. Point-of-Care Ultrasound —History, Current and Evolving Clinical Concepts in Emergency Medicine. Medicina, 59(12), 2179.

2. Schwarz et al. Experience rounding with a hand-held two-dimensional cardiac ultrasound device. The American Journal of Cardiology, 62(1), 157–159.

3. Heller et al. Ultrasound use in trauma: The FAST exam. Academic Emergency Medicine: Official Journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, 14(6), 525.

4. Akhtar et al. Resident Training in Emergency Ultrasound: Consensus Recommendations from the 2008 Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors Conference. Academic Emergency Medicine, 16(s2), S32–S36.

5. Lewis et alCORD-AEUS: Consensus document for the emergency ultrasound milestone project. Academic Emergency Medicine: Official Journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, 20(7), 740–745.

6. Amini et al. Ultrasound competency assessment in emergency medicine residency programs. Academic Emergency Medicine: Official Journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, 21(7), 799–801.

7. Ahern et al. Variability in Ultrasound Education among Emergency Medicine Residencies. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 11(4), 314–318.

8. Lichtenstein et al. Lung ultrasound in the critically ill. Annals of Intensive Care, 4(1), 1.

9. Mojoli et al. Lung Ultrasound for Critically Ill Patients. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 199(6), 701–714.

10. Lichtenstein et al. BLUE-protocol and FALLS-protocol: Two applications of lung ultrasound in the critically ill. Chest, 147(6), 1659–1670.

11. Ovesen et al. Point-of-Care Lung Ultrasound in Emergency Medicine: A Scoping Review With an Interactive Database. Chest, 166(3), 544–560.

12. Pang et al. Lung Ultrasound-Guided Emergency Department Management of Acute Heart Failure (BLUSHED-AHF): A Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial. JACC. Heart Failure, 9(9), 638–648.

13. Kim et al. Experience with emergency ultrasound training by Canadian emergency medicine residents. The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 15(3), 306–311.

14. Apiratwarakul et al. Assessment of Competency of Point-of-Care Ultrasound in Emergency Medicine Residents during Ultrasound Rotation at the Emergency Department. Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences, 9(E), Article E.

15. Russell et al. External validation of the ultrasound competency assessment tool. AEM Education and Training, 7(3), e10887.

16. Elsayed et al. Emergency medicine trainees’ perceived barriers to training and credentialing in point-of-care ultrasound: A cross-sectional study. Australasian Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine, 25(4), 160–165.